Mr. Wicker (EBOOK)

In the heart of a Dallas summer, a menacing figure descends onto the concourse of the Mellows Subway Station, dragging a veil of darkness behind him. Escaping beyond the veil proves deadly: a woman loses her life upon crossing, while another loses a hand. The station is sealed off from the world—a private prison made of shadow and concrete. And there, shrouded by the gloom, the malevolent Mr. Wicker lurks, a spectral sentry whom none shall pass.

No one dares to cross beyond the veil, and no one knows if they’ll ever escape.

Warren Dodd, an ex-con hoping to be reunited with his family after seven years behind bars, finds himself trapped in the company of a cluster of equally unlucky citizens—an insurance salesman with a chip on his shoulder, a duplicitous attorney, a busker in mental anguish, Warren’s wife and child, and a Chinese national running from her past. And nobody is entirely who they seem …

The group faces a grim choice: decipher the meaning behind Mr. Wicker’s presence, or forfeit their lives to the dark.

And with the veil drawing ever closer, time is running out …

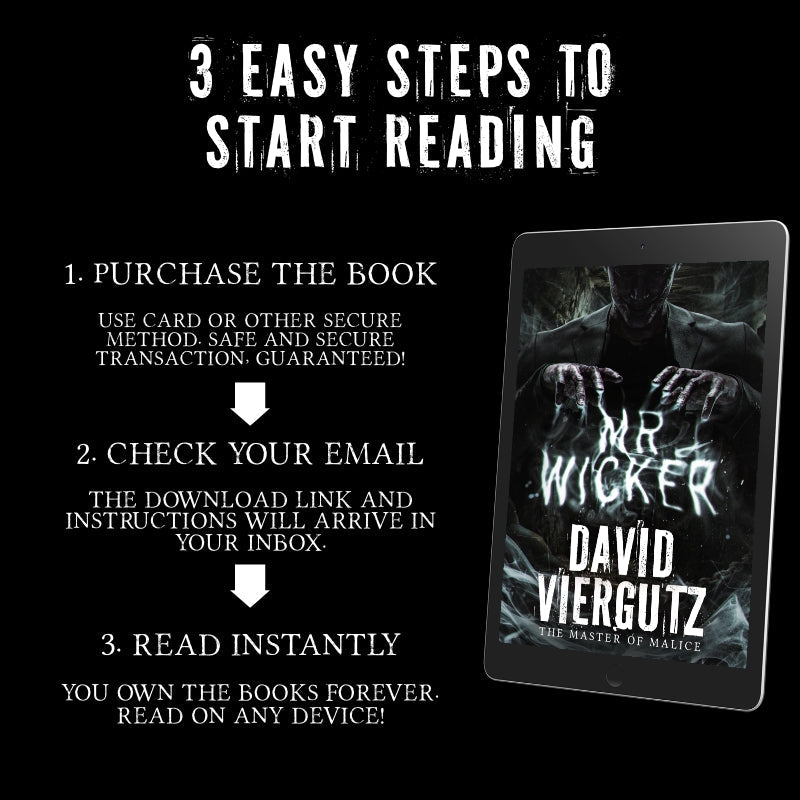

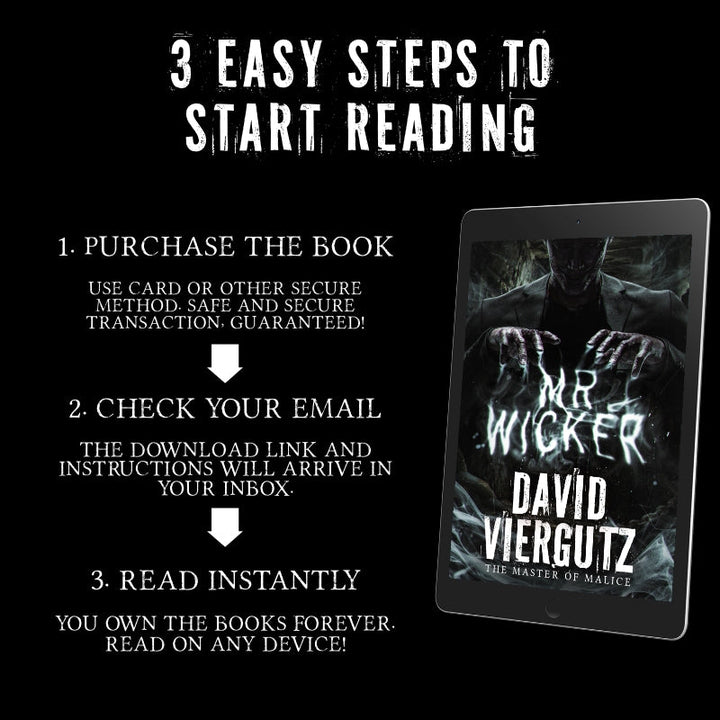

Ebook, delivered by Bookfunnel, read on any device.

Print books shipped from my independent printer.

Ebooks and audiobooks are delivered by email through Bookfunnel. Check your email and then download or read listen on your favorite device.

You can read the ebooks on any ereader (Amazon, Kobo, Nook), your tablet, phone, computer, and/or in the free Bookfunnel app.

Chapter 1: Warren Dodd

The city of Dallas was ablaze.

Towers of steel and concrete, backlit by rays of amber and gold—the last remnants of another day having passed—surrounded Warren Dodd like the oppressive overwatch of the towers at Redwinds State Prison, no more than three miles in the opposite direction. He’d left the prison in his wake, adopting a dreamy, excited gait that carried him from the prison to a motel for three nights, paid for with what remained of his commissary. The hotel was fine: the sheets were mostly clean, and the glare of flashing police lights had only woken him twice during his stay. On the third day, Warren had filled his pockets with bagels and packets of ketchup―for he had taken all of the grape jelly the day prior―and left for his final destination.

A subway station a quarter mile away.

At the corner of Sixth and Federer, a crowd had gathered, awaiting the changing of the guard—the street sign that dictated when to move and when to wait. Harried men in prim suits and pressing expensive cell phones to their ears risked the stampede of traffic, for the drivers of Dallas merely saw pedestrians the same as they would a gnarled branch on the road: as an inconvenience.

Warren waited patiently, the soles of his feet warm through his shoes from the pavement. It was mid-August, which actually meant nothing in Dallas: the weather cycled through hot to hotter and then back to hot for most of the year. The climbing temperature didn’t bother Warren; over the last few years, he had only experienced the occasional summer storm and otherwise refrigerated temperature within the concrete prison walls, either a product of design or the literal “cooling off” of the inmates, as energy was spent keeping warm rather than fighting.

Another suit pressed against Warren, briefly glancing at the exposed tattoos on his arm before his eyes widened and he clutched his briefcase closer to his chest. The suit turned away like a dog caught drinking from the toilet bowl.

Warren ignored him; he was used to the looks. What he wasn’t used to was the sense of urgency these city folk had; the way they flicked their wrists to glance at expensive watches with worried eyes or tapped their phone screens―once, twice, three times―looking for messages or emails. Warren had never shared the same sense of simmering focus, dictated by the idea that they might miss an important update or that time itself would turn on them and leave them pleading for their job as they explained away their tardiness at some all-important meeting.

Warren looked up, counting sixteen stories before he got dizzy. Near the top, a glass window looked out upon the world. A man reached over the chasm and drew in the window, paying no mind to the specks marching dutifully up and down the street below.

At Redwinds, the only urgency had come from the guards themselves as they’d exchanged keys, paperwork, and glances on their way out the door.

On his first night―the coldest, while his sentencing had still felt like a fever dream and reality had set in―Warren had asked one of the more approachable guards, a man the others called Shrink—the moniker earned due to his undeterred desire to converse with anyone who dared to sit next to him—if he felt like he, too, was in prison. Shrink recognized that the only real difference between the guards and the prisoners were that the guards got to leave for a few hours each day. The chatty correctional officer continued to explain that he could understand why some of his colleagues might feel that way, but his own experience within the prison was inherently different—and it came from having someone to go home to; in his case, a twelve-pound tabby cat named Socks.

Shrink and Socks. Perfect.

Warren had liked their conversations; it was as close to a real friendship as he could imagine inside Redwinds’ walls. They’d spoken about mundane things, their chatting nearly normal—just two men shooting the breeze about life, values, and politics―only, at the end of the conversation, Shrink would go home to Socks and Warren would drag his feet up the cold, grated stairs to Cell 213.

Shrink was never urgent; he simply came and went. Warren, however, learned that urgency had no place in prison―time was, after all, something inmates had in abundance―and that same realization was the only thing besides the clothes on his back that he’d carried out the front gates of Redwinds three days prior. He would never forget Shrink and Socks, though.

The transition from life in prison to the daily hustle was going to be challenging. In that moment, Warren understood why men with much more to lose than he might consider a parachute-less belly flop from a skyscraper window.

The signal changed. Warren, now one with the throng―an amorphous wall of navy and black suits―moved across the street. In the sea of dark polyester, he stood out. Warren wore a white T-shirt, the armpits yellowed from sweat and the collar pockmarked with tiny holes where the fabric was starting to wear. Adding insult to injury, his arms poured sweat into the fabric, thinning it while reactivating ancient body odor soaked deep into the threads―but it wouldn’t be the foulest smell he’d suffer while walking the city streets.

The shuffle merged with another horde of bobbing heads approaching from the opposite direction and Warren stepped to the outside, narrowly avoiding the bumper of an oncoming Nissan with a dent in the hood that looked suspiciously shaped like a human.

The man with the briefcase brushed his elbow and, reflexively, Warren lurched, his senses coming alive, only to have reality rush toward him like a screaming train.

You’re okay. This isn’t Redwinds.

A brush of the elbow was how a fight started in prison: first, the elbow, then the inevitable shoulder throw and, finally, the cold slip of a shank made from melted plastic and an affixed razor blade that came from the side, wielded by a buddy of the elbow-thrower. It was a swift move, and minutes would pass before guards were summoned to a near-death inmate clutching his ribs in a pool of blood among thirty witnesses who conveniently saw and heard nothing.

For a moment, Warren’s fight-or-flight response brought on new waves of panic and the taste of copper on his tongue. Gasoline, hot asphalt, and the scent of baked trash assaulted his senses. He waited for the cold slip of the knife …

But it never came. The elbow brush was just an accident, and the world continued to turn.

Although he was free of the prison, Warren already felt other walls closing in. They were walls built within his own head, cemented with fear and angst and worry, and the further Warren walked toward his destination―a free man, but no less a convict―he felt the reins of reality tightening a noose around his neck. Being plucked from prison and released back into society felt every inch like stepping out of the frying pan and into the fire.

On the other side of the street, the crowd dispersed in several directions and the traffic resumed. Warren read the sign posted on a streetlamp in front of a swanky outdoor bar partitioned by a waist-high wrought iron fence.

Mellows Station—straight ahead. 3 miles.

Nervous men stood over tables, talking to pretty young things in tiny dresses who dismissed their every advance with rolling eyes and hair tosses. Warren could smell the alcohol emanating from their pores. Post prison, everything smelled strongly now.

He avoided the bar and moved out into the street, crossing before the light could change, and poked his head in the open door of what appeared to be a less popular, slightly dingy bar. Smoke clung to the ceiling, and a steady bassline rattled the glasses hung above the counter. A fluorescent clock on the wall read 7:15 P.M.

Warren continued down the sidewalk.

He had time to stop off, but there was no way he was missing this meeting. He’d waited seven years for tonight: seven years and three days of wondering and hoping and penning letters that were eventually never returned. In the last year before his release, the reply letters had stopped coming, and he’d got by, by telling himself there was a problem with the post, that somebody had stolen his letters or his wife was just busy and a flood of them would arrive shortly. This hope had continued for days, which bled into weeks and, finally, months. Still, he’d held onto hope, and only once release day approached and he was ushered into the empty waiting room and handed a plastic bag with the clothes he now wore did he lose that hope he’d carried with him. All that had remained was his determination to find out why.

After misjudging an uneven stretch of sidewalk, Warren’s left shoe connected with a fissure in the concrete and came loose, flung from his toes. The shoes―orange sponge-like clogs that all the prisoners wore―were three sizes too big. Prior to leaving Redwinds, he’d forgotten that he hadn’t entered the prison with shoes on his feet. As he’d faced the possibility of searing off pockets of skin on the burning concrete, heated by the scorching Texas sun, Shrink had noticed Warren’s apprehension at the front gates and had promptly brought him the oversized shoes. They had been thrown away—a broken strap on the left foot that was soon to be the bane of his existence if it came off just one more time. When Shrink had handed him the shoes, Warren had given him a nod of understanding, a final communication wishing him good luck, Godspeed, and don’t-you-fucking-come-back. Warren had taken the shoes with grace, but the gesture had reminded him of his mother in a way, who would often scold him when he was a boy for taking his shoes off in the car.

* * *

“You put your shoes on, Mr. Warren Dodd.”

“I want to leave them off for now, Momma. They’re too small,” Warren pleaded, massaging the tips of his blistering toes.

“Your shoes are fine, Warren―now, put them on! Put them on because I don’t want to smell your dirty little feet. You don’t want your feet to get dirty, do you, Warren?”

He hated the way his mom said “dirty.” She spat it out, malice in every syllable, the words slithering between her rotten teeth.

Calissa Ray Dodd was serpentine. A vile woman of pallid flesh and bulbous eyes, her bones were brittle, and her skin bruised easily. She blamed anemia, but Warren didn’t know what anemia was. She blamed anemia, and Warren hated anemia for hurting his mom.

* * *

It had been always anemia with Calissa, because anemia wasn’t her fault.

Later, Warren grew to know better.

His mind recalled one hot afternoon in July―memorable because of the tubular remains of the Fourth of July fireworks that had littered the cul-de-sac―seen through the large picture window on the first floor of the Dodd family home. Warren remembered sitting on the crumby sofa―a dark green hue that easily hid the stains―and watching a cartoon series about robot colonies who eventually took on an empire. He’d dug his feet between the cushions, like most kids did, until his big toe had touched a little glass pipe, and anemia made sense no more.

In his mom’s dictionary, anemia was another word for “dope”, and the little glass pipe was her “medicine.” The kids who’d lived in Warren’s neighborhood had explained to him that drugs were bad, but finding that little glass pipe reeking of wacky baccy had allowed him to assume his mother’s belligerent behavior toward him was the result of her addiction—her sickness. The kids had promptly suggested he smash the pipe and sweep away the evidence into a blue dumpster near the park.

Warren had thought he was helping her. He’d thought he was curing her addiction because without the pipe to deliver the “medicine,” she’d be forced to quit.

He was wrong.

Later that day, Calissa had returned home, hunting, searching, fiending for her “medicine,” a rabid, twitchy dog that stalked the house with her hands curled up to her chest, like a witch.

Warren had cowered on the couch, pretending to read a book but watching the snakelike woman scour the living room with growing ferocity, her nose upturned and her eyes like wide glass orbs.

“What are you looking for, Momma?” he’d asked, attempting to clear the palpable tension wafting from his mother’s body like an aura.

“A little glass tube,” she’d replied snappily, ripping up the couch cushions and tossing them aside with Warren still sat atop them. He’d fallen onto the cold springs below, her strength surprising him.

“A white one with a bulb on the end?”

His mother had whirled to face him. “How do you know that?”

Warren remembered his heart leaping into his throat and settling under his chin. He remembered ducking behind his book―a picture book about dinosaurs that looked mean but actually ate leaves. He couldn’t remember the name of them, but they had beaks and a curved horn protruding from the back of their head. What was their name? But the words beneath the images might as well have been hieroglyphs―he hadn’t really been reading at the time.

His mother’s eyes had been like daggers. “What did you do? Tell me where you put it, you little worm.”

Warren had peered over the top of his book in time to see his mother’s bony, pale fingers, skeletal limbs clamp around his throat, her nails, filed to a point, digging into the soft flesh around his Adam’s apple. His head had felt like it was about to pop as the blood was caught either side of her fingers, his heart continuing to pump wildly.

“Tell me, you little shit!” she’d screamed.

Warren remembered a ripe fear taking ahold of him. It had weakened his bladder and choked him more than his mother ever could. As warm urine had run down his leg and soaked into the already rancid couch, Calissa had looked down.

“Oh, you disgusting boy! You disgusting, dirty, dirty little boy!”

Warren’s mother had released his throat only to clamp her vice-like hand around his penis, squeezing and pulling while she’d bellowed into his face with her swampy, sour breath, her nails digging into the tender skin.

“Tell me where it is, you filthy little boy!”

Between squeals and blinding, embarrassing pain, Warren had cried, “I smashed it! I smashed it!”

Releasing his privates, she’d backed off, wiping the sweat that had frizzed her hair and hung in little drops on the micro-hairs atop her thin, scabbed lips.

Warren had scampered into the corner, attempting to make himself as small as possible, sniffling, too scared, too terrified to cry, through fear that even the sound would only enrage her further. Calissa had hung her head in thought, her hands on her hips, then, from under her brow, she’d eyed him with the most devilish, predatory look.

She’d lurched forward, latching onto his shoes and ripping them from his feet while Warren had yelped and ducked behind his knees, quivering.

“Jen has a snotty-nosed kid your age. These will probably fit him. She’ll probably give me a few bucks for them to replace my pipe, you dirty, dirty boy.” She’d scoffed and futilely straightened her wispy hair. “Clean up before I get back, Warren Dodd. Spray the couch down and throw your clothes away.”

“Throw them away?”

“Yes, they’re soiled! Ruined with your rank piss, you little brat! Only clean boys get clothes and shoes.”

She’d stopped in the doorway, his shoes in her hands, and peered around the door. Her face had changed—it had lightened somehow.

“I love you, Warren,” she’d whispered. “I always will.”

Warren remembering crying silently to himself as he’d peeled off his shirt and pants and tossed them onto the floor.

Calissa had shut off the lights and locked the door behind her. Once she’d left him, totally naked and in the dark, Warren had taken comfort in the knowledge that he’d prevented his mother from using for just a few extra minutes—and that night, for the first time in months, she’d said she loved him.

Standing naked, embarrassed, and reeking of his own piss, it had been a welcome price to pay just to hear, “I love you, Warren.”

* * *

Warren ripped himself from the memory with a strong exhale through pursed lips. He retrieved his errant shoe and slipped his foot forward into it, curling his toes near the front to keep it on. He could walk, but the going was awkward and slow. He’d limp every mile if he had to. He’d glue the fucking shoe to his foot before he let it come off again.

There was no way he was missing this meeting—and there was no way his shoes were coming off his feet.

He wasn’t a dirty boy.